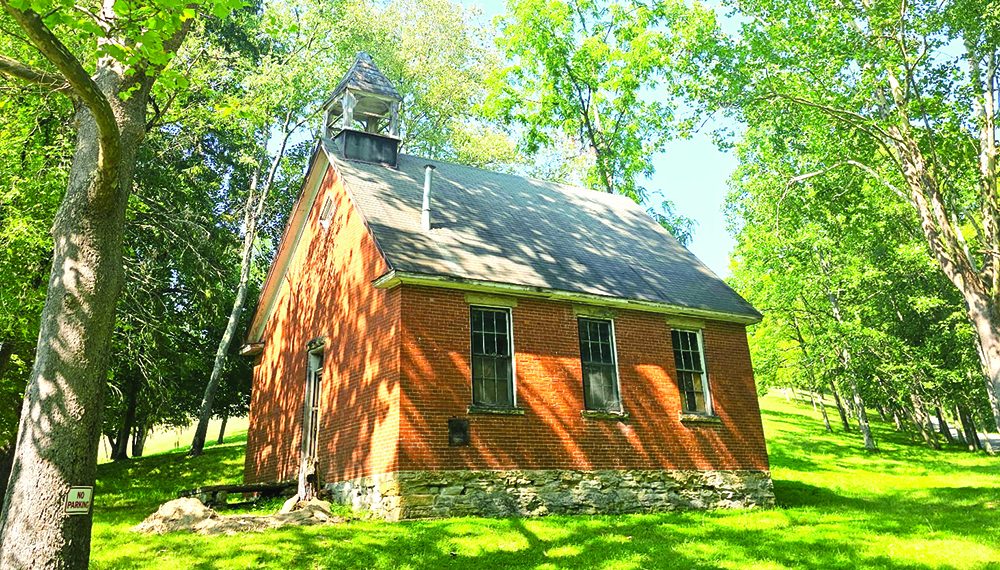

Deep in the valleys of Southwestern Pennsylvania, lay hidden gems. The old, red brick one-room schoolhouses that accommodated so many children of this isolated region of Appalachia can still be seen across the county.

Such a very important part of our county’s history is silently hushed, resting amongst the hillsides and vast forests that surround us. These beautiful, hand-crafted buildings are still visible today and should be rediscovered and restored for many generations to come.

It’s not hard to imagine children leading their younger siblings down long dirt roads in the cold winters to find warmth in the schoolhouses.

Working hard inside were the teachers, who not only educated, but swept and cleaned the floors, and started the fires that kept the children warm during those long, frigid months.

Those beautiful women of the community could multi-task well, teaching grades 1-8 without pause. The basics of reading, writing and arithmetic were essential to function in the everyday community in which they lived. These skills not only maintained the foundation of everyday life but also helped to expand the surroundings of their ever-growing community.

Local families funded these schoolhouses, and they were often used for more than just education. The schoolhouses also functioned as celebration sites, polling places, and even churches on Sundays.

Desks were arranged in group levels, and the eldest of the students were expected to help with teaching the younger grades. Typically, on the walls at the front of the classroom would be maps of the larger world that surrounded these children. A globe would teach them the Earth was certainly not flat, and a chalkboard provided a place for grammar and math lessons.

The history of the nation in which they lived was also essential. To quote the late, Al Deynzer, who was a pillar of Greene County, “If you don’t know where you came from, how do you know who you are?”

The children were required to start with the Pledge of Allegiance. Patriotism and prayer were part of these powerful life lessons.

Steve Simms, a resident of Aleppo Township and retired PennDot worker, recalled his days in one of the structures.

“The Aleppo schoolhouse had a six-man football team that played offense and defense. Richard Simms, John Watson, and Jimmy Ullom were the stars. They would compete against the other school kids, and boy were they a something.”

He also spoke of his friend Bob Jones, who gave the children of the Aleppo schoolhouse oranges for Christmas. Many of the kids had never seen, nor eaten an orange in their lifetimes. It was quite a gift.

Another resident, Paul Braddock went to the one-room schoolhouse on Long Run Road in 1946. He spent his first two years of schooling there. It was a little, wooden frame building that sat behind the Long Run Church of God. The school is long gone, and the church has unfortunately been vandalized and left in ruin.

Braddock, who is still a State Farm Insurance agent, recalled fondly, “My mother started me a year early because I begged to go with my brother, who was two years older than me. When we got there in the fall of 1946, the leaves were already turning. I walked in the schoolhouse, and the teacher was stoking the cast-iron potbelly stove that sat in the middle of the room.”

He continued, “When us kids had an argument, disputes were settled at the coal house.” That was where the coal was kept outside in a small shed. Fisticuffs were not an everyday occurrence but did happen to settle arguments.

Braddock also chuckled as he recalled when one of his classmates, Lee Jackson, who was tall for his age, took the paddle off the wall and held it high in the air so the teacher could not use it on him. All the kids laughed, although the teacher was not so amused.

The Greene County Historical Society is also a perfect place to start your own research.

Though they no longer provide housing for education and other events, the one-room schoolhouse reminds us how to excel with limited resources. These tight-knit, intimate settings provided wonderful environments and education for those that became pioneers for their community for many years to come.

In what state is the schoolhouse now? Is there any way to restore the structure as a museum of the past? Waynesburg University students might be interested in using this as a project to work on for the community. Especially as it is so close to campus and the Alston farm, now owned by the University.